Since the beginning of the year, we’ve been monitoring the economic recovery of 10 coastal towns with our Coastal High Street Tracker, which we’ve developed in partnership with Power to Change and the Architectural Heritage Fund.

In case you haven’t checked out the tracker, it displays granular spending data on a set of 10 coastal towns in England that have received substantial social investment and grant funding from each funder: Birkenhead, Great Yarmouth, Grimsby, Hastings, Hartlepool, Margate, Morecambe, Penzance, Plymouth and Redcar.

Over the past six months, we’ve gone from a full lockdown to partial reopening – and with ‘Freedom Day’ now delayed by a further four weeks, it feels like a good time look back at the data and see what it is telling us about how these towns are bouncing back from the last year of Corona Shock.

1. There are signs of exaggerated seasonality in seaside resorts

The latest data release for May 2021 has begun, for the first time, to show a clearer split between seaside resorts (those who’s seasonal economy is predominantly reliant on tourism) and other coastal towns.

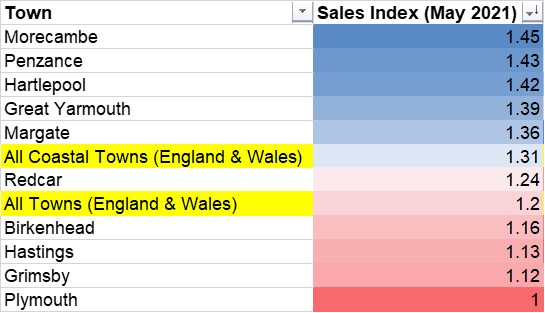

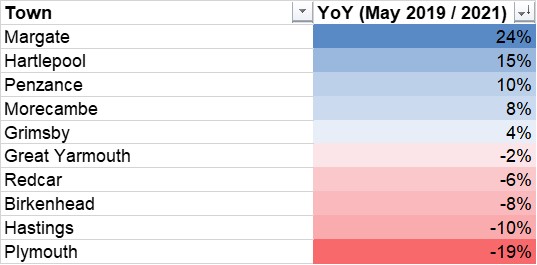

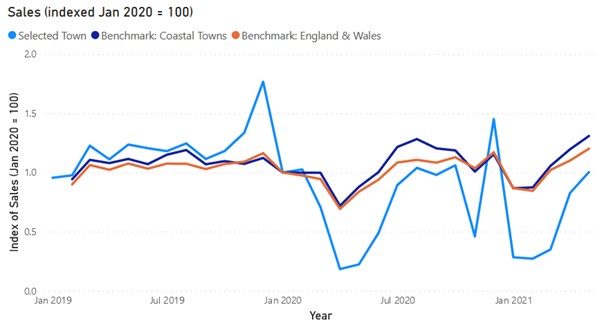

Figure 1: Sales Index for May 2021, where 1 = local spend in January 2020

Morecambe, Penzance, Great Yarmouth and Margate are all outperforming the benchmarks on the sales index (and the ‘all coastal towns’ benchmark is also outperforming England and Wales aggregate too). This is what we might expect with two May bank holidays, improved weather (at least towards the end of the month), and less foreign travel boosting domestic tourism in these seaside destinations. Coastal towns – e.g. Birkenhead, Grimsby, Plymouth – on the other hand are performing less well relative to the seaside resorts, but equally they have somewhat less seasonal local economies.

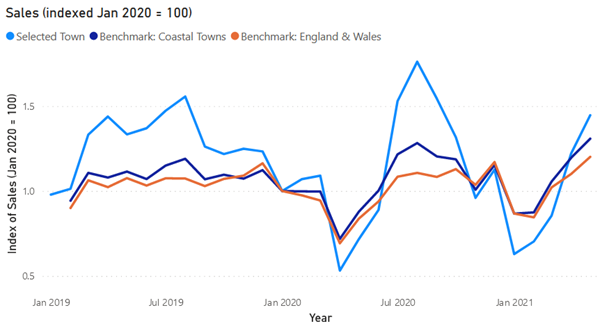

The pattern emerging seems to show that seaside resorts have generally had deeper comparative drops during both lockdowns, but last year during the summer these began to significantly outperform the benchmarks and other coastal towns. This same trend appears to be repeating itself as we enter the summer months again this year. A seasonal local economy may mean that these seaside resorts experience a small boom over the summer, but the more severe collapse in spending during lockdowns does emphasise the unsustainability of an economy so dependent upon retail, tourism and hospitality. Diversifying these seaside economies to be less reliant on seasonal trade and more self-sustaining will be an important part of building resilience post-Covid.

2.A by-election boost for Hartlepool?

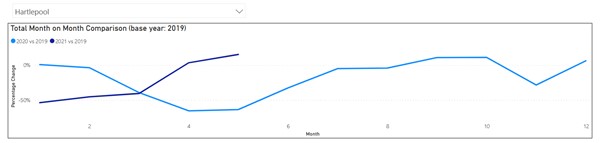

The notable exception at this stage of course is Hartlepool – which is outperforming the other coastal towns and saw a significant surge in spending throughout May: 15% higher than 2019.

Could this be a direct effect of the Parliamentary by-election on 6 May which is likely to have drawn in significantly more visitors – politicians, activists, and journalists, for example – than would be usual for this time of year? Or is it simply that we are seeing the release of pent-up spending from residents who are choosing to use their local high streets more often than they were previously? And if the latter is the case, then why is this effect more pronounced in Hartlepool than, say, Birkenhead or Grimsby?

We will continue to monitor these spending flows to see whether this surge in Hartlepool is sustained over the summer, which will help contextualise this data and build a better understanding of what is happening and why.

3.The recovery is not uniform…

The YoY comparisons (for May 2021 vs 2019) show a slightly different picture for the seaside resorts than the sales index. Margate has seen a very large YoY increase (something that can perhaps to be expected given the proximity to London, with people taking day trips during the bank holiday weekends), whereas Great Yarmouth has essentially just seen a return to normal spending levels in May. Oddly Redcar, which was an early outlier in having a smaller hit to its local economic activity at the beginning of the year, is the only town to have seen a falter in its recovery, having moved from 2% in April 2021 to -6% in May 2021.

4. … and some places are experiencing ‘economic long Covid’

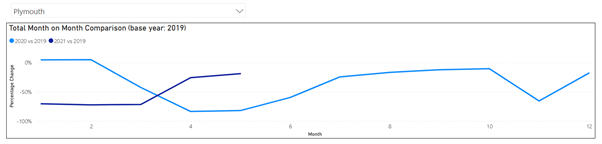

The data is most concerning for Hastings and Plymouth, both of which haven’t really recovered at all this year. If spending levels in Plymouth continue to follow a similar trajectory to 2020, it could be that the town does not reach the 2019 baseline for almost two years.

This is even more striking when you look at the longer time series for Plymouth and see that spending was relatively buoyant pre-pandemic. The length and severity of this recession is going to have a significant impact on local businesses. It is almost as if Plymouth’s high streets are experiencing an economic form of long Covid.

So, what does this mean for our high streets?

Over the course of this year, as restrictions have been slowly lifted, we’ve begun to see some clearer divergence between the towns. The significant disparities between even this small subset of coastal towns emphasises the importance of place when thinking about our Covid response.

Some high streets, like those in Plymouth, have been in recession since March 2020 and this will have put serious pressure on local businesses. The government support schemes – including the furlough scheme and direct grants – might have helped them to stay afloat thus far, but as these taper off at the end of the year there is a real danger of a rise in insolvency and job losses – especially for businesses that have taken on substantial amounts of debt during the pandemic. This is why we’ve been running a campaign exploring how an innovative debt-for-equity fund could help to ease the SME debt burden, while creating a more inclusive economy by facilitating a transition to more social business models like employee, worker or community ownership.

However, we still don’t really understand why there is this divergence between different towns. Further analysis of the data might be able to tell us whether high street composition matters for recovery: are the places that are struggling to bounce back those that have an oversupply of high street retail and shopping centres? Is the stronger recovery found in places with mixed use, independent high streets with more leisure and experiential offerings? These are important questions to answer, particularly for those interested in the future of the high street and how we might genuinely build back better from this crisis.

Photo credit: Kai Bossom on Unsplash